Knee Articular Cartilage Injury

Knee Articular Cartilage Injury

The lower end of the femur (thigh bone) and the upper end of the tibia (shin bone) come together to form the knee joint. The ends where these bones converge are blanketed in a shiny and smooth white tissue known as articular cartilage. This connective tissue aids in joint movement and protects the ends of the femur and tibia when gliding over one another. The articular cartilage can become damaged from normal “wear-and-tear” or injured in a traumatic event. The most common pathology involving the articular cartilage of the knee is osteoarthritis- a longstanding degeneration of this tissue. This condition tends to become symptomatic later in life after several years of inflammation in the knee joint. Additionally, the cartilage all throughout the knee joint often undergoes degeneration in this condition (as opposed to a single isolated location of cartilage breakdown).

Younger patients, however, may experience focal articular cartilage damage from a specific injury such as a knee dislocation, ligament tear, or meniscus tear. In these cases, patients can experience significant pain and inflammation from their cartilage injury which limits their mobility and ability to perform activities they enjoy. Importantly, the cartilage injury in these cases is isolated to a single part of the knee (as opposed to the entire joint as with the case of osteoarthritis). This is an important distinction as it relates to treatment options. Whereas diffuse osteoarthritis is often treated surgically with total knee replacement, focal cartilage defects in an otherwise healthy knee can often be treated with joint-preserving techniques.

Orthopedic Surgeon and Sports Medicine specialist, Dr. Jonathan Koscso, successfully diagnoses and treats patients in Sarasota, FL and the surrounding Gulf Coast region who have experienced an articular cartilage injury.

Symptoms of an Articular Cartilage Injury

Focal articular cartilage injuries are generally associated with a single, discreet injury and tend to occur in younger patients (i.e. a football player being tackled and tearing their ACL and a meniscus, or a tennis player pivoting during a backhand and experiencing sharp, sudden pain in their knee). Often, a cartilage injury diagnosis is made while evaluating the knee for other ligament injuries in this regard. Once present, cartilage injuries are associated with achy pain in the knee that tends to flare up after bouts of heavier activity. Additional symptoms of cartilage injuries include:

Swelling and stiffness in the knee

“Locking” or “catching” of the knee

A “pop” can sometimes be heard with a given injury

Decreased knee range of motion

To diagnose an articular cartilage injury, a comprehensive medical history, including how the injury occurred, will be performed by Dr. Koscso. A physical examination will be performed involving an evaluation for areas of pain and tenderness and range of motion will be assessed. Diagnostic imaging, such as x-rays and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), will likely be requested to determine the extent of the injury and confirm a cartilage injury diagnosis. MRI is often additionally helpful in identifying any other associated injuries to the knee.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Initial treatment for articular cartilage injuries focuses on pain relieving measures and restoration of knee range of motion. Conservative therapies such as rest, ice, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications are recommended to reduce inflammation in the knee. Small, non-displaced cartilage defects may be further managed non-operatively with an appropriate course of physical therapy to strengthen the knee before returning to sport. Occasionally, biologic injection therapies- namely platelet-rich plasma- may be utilized to augment tissue healing and optimize the overall health of the knee cartilage.

Surgical Treatment

In the event of significant articular cartilage damage, or in patients who are still having symptoms despite the above conservative measures, surgical intervention may be required to restore the articular cartilage. Of note, patients who have experienced a single cartilage defect or injury are more likely to benefit from surgical restoration than those with multiple cartilage lesions. There are several surgical techniques that can be utilized to restore the articular cartilage. These restoration techniques are tailored to each patient’s specific injury or cartilage defect and should only be performed by an experienced orthopaedic knee surgeon. Dr. Koscso may employ one of the following restoration techniques:

Chondroplasty: This procedure, also known as debridement, simply excises and removes the damaged cartilage to reduce the pain and inflammation associated with this condition. This is a helpful procedure in patients with lesions that cause mechanical locking of their knee. Of note, however, the underlying cartilage damage is not repaired or restored. Younger patients with full-thickness cartilage defects are typically not candidates for this technique.

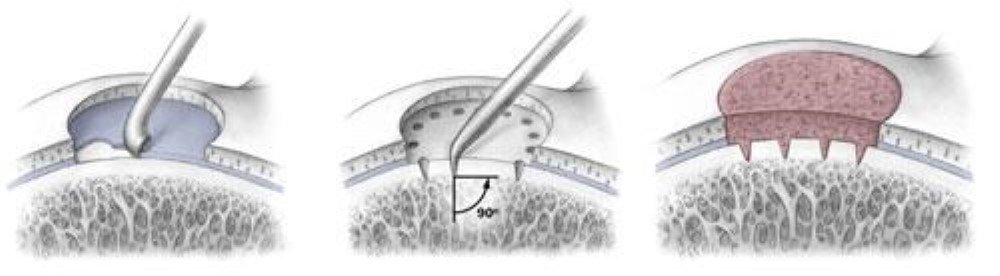

Microfracture: This technique utilizes a sharp surgical instrument to create openings within the base of the lesion to produce the natural healing response of a bone bleed. The cells from the blood supply permeate the damaged cartilage and harden into new cartilage. Dr. Koscso will often only employ this restoration technique as a last resort, however, because recent studies have shown that the cartilage generated from microfracture is not as durable at bearing weight as native cartilage.

(Left) Graphic representation of microfracture procedure, in which the underlying surface of a cartilage lesion is debrided of the calcified cartilage layer; multiple 2mm holes are then made at the base of the lesion to allow the deeper bone marrow elements to fill the lesion; in the months following the procedure, the marrow elements will transition into fibrocartilage tissue. (Right) Arthroscopic image of a prepared lesion after multiple microfracture holes have been made at the base of the lesion, but before the surgeon has turned off fluid inflow into the knee (which would allow the marrow elements to fill the lesion).

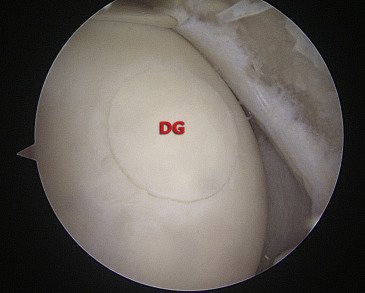

Osteochondral Autograft Transfer Surgery (OATS): This procedure harvests a healthy cartilage graft from a separate part of the patient’s own knee, which is then moved to the specific areas of damaged cartilage. The cartilage harvest is done at an area of the knee that does not bear weight or articulate with any bones during knee motion (i.e. it is “expendable” tissue). This surgical graft eventually incorporates into the underlying bone where it is transferred and, thus, becomes the “new” cartilage at the site of the previous lesion. OATS is an excellent option for cartilage defects with promising outcomes in the orthopaedic literature. The limiting factor to the procedure, however, is that it can only be used for relatively smaller lesions in the knee (since your knee has only so much “extra” cartilage tissue to serve as the donor graft).

(Left) Graphic representation of osteochondral autograft transfer surgery (OATS) in which two osteochondral donor plugs have been harvested from the lateral femoral condyle and transferred to a defect in the medial femoral condyle. (Right) Arthroscopic image of a completed OATS procedure with the donor graft (DG) sitting flush with the surrounding intact cartilage.

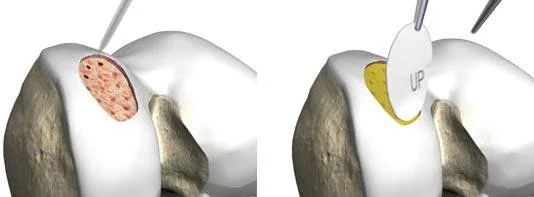

Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation Surgery (OATS): This procedure differs from the above autograft surgery only in that it involves a harvest of a cartilage graft from a cadaveric donor (rather than from a separate part of the patient’s own knee). This surgical graft provides a surface for new cartilage to grow and ultimately restore the damaged tissue. The benefit of allograft transplant, as opposed to autograft transfer, is that the technique can be used for larger knee lesions since we can take a somewhat unlimited amount of donor tissue from the cadaveric specimen.

Osteochondral allograft transplant procedure in which the native lesion is prepared (A), a donor plug is harvested from a cadaveric femoral condyle (B), the graft is confirmed to size appropriately to the recipient site on the patient’s knee (C), and it is implanted into place to serve as the “new” cartilage (D).

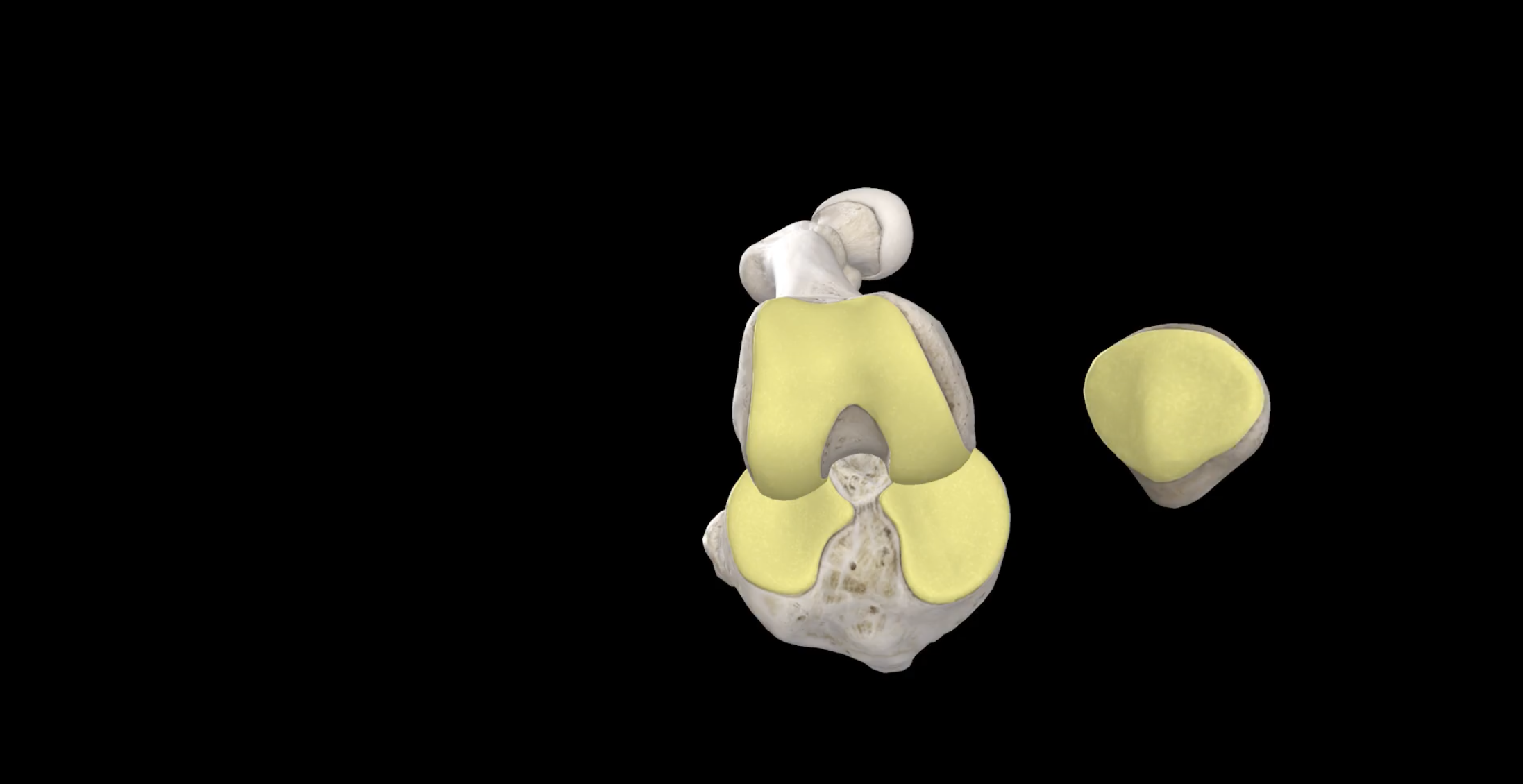

Matrix-Induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI): This technique involves two stages. First, a biopsy of healthy cartilage from the patient’s knee is removed via a minimally-invasive arthroscopic surgery, and this tiny fragment of cartilage is grown in a lab. The expanded cartilage cells are secured onto a biologic scaffold tissue which is then implanted into the patient’s knee during a second surgery.

(Top) Graphic representation of 2nd stage of MACI procedure in which final implantation of the cartilage-containing biologic scaffold occurs. In the months following the surgery, this tissue grows to become healthy hyaline cartilage (bottom).

Post-Operative Recovery

For a comprehensive reading of the expected post-operative recovery, including restrictions, physical therapy progressions, and return to work/sport guidelines after knee articular cartilage repair surgery, please see our corresponding protocol on our physical therapy protocols page. Note that the specific protocol is dependent on which of the above procedures was performed and which aspect of the knee joint underwent repair.

About the Author

Dr. Jonathan Koscso is an orthopedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist at Kennedy-White Orthopaedic Center in Sarasota, FL. Dr. Koscso treats a vast spectrum of sports conditions, including shoulder, elbow, knee, and ankle disorders. Dr. Koscso was educated at the University of South Florida and the USF Morsani College of Medicine, followed by orthopedic surgery residency at Washington University in St. Louis/Barnes-Jewish Hospital and sports medicine & shoulder surgery fellowship at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City, the consistent #1 orthopaedic hospital as ranked by U.S. News & World Report. He has been a team physician for the New York Mets, Iona College Athletics, and NYC’s PSAL.

Disclaimer: All materials presented on this website are the opinions of Dr. Jonathan Koscso and any guest writers, and should not be construed as medical advice. Each patient’s specific condition is different, and a comprehensive medical assessment requires a full medical history, physical exam, and review of diagnostic imaging. If you would like to seek the opinion of Dr. Jonathan Koscso for your specific case, we recommend contacting our office to make an appointment.