Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injury

Ulnar Collateral Ligament (UCL) Injury

The medial ulnar collateral ligament is an important structure on the inner aspect of the elbow that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) to the ulna (one of the forearm bones) and is crucial in providing stability to the elbow during sporting activity. Injury to the ligament can occur in athletes who place excessive loads across the medial aspect of the elbow. This is classically seen in overhead athletes- often baseball pitchers- and has led to one of the most popularized surgeries in all of sports, “Tommy John surgery.” Any throwing athlete, however can sustain this injury including softball players or javelin throwers. Additionally, gymnasts and cheerleaders tend to place high compressive loads across the medial elbow during activities such as tumbling and are at risk of injuring the UCL.

Orthopedic Surgeon and Sports Medicine specialist, Dr. Jonathan Koscso, was a former team physician for the New York Mets during his Sports Medicine Fellowship training at the Hospital for Special Surgery and routinely evaluated and treated baseball players at the highest levels. Accordingly, he has a strong clinical interest in diagnosing and treating patients in Sarasota, FL and the surrounding Gulf Coast region who have experienced an elbow ulnar collateral ligament injury or other overhead athlete conditions.

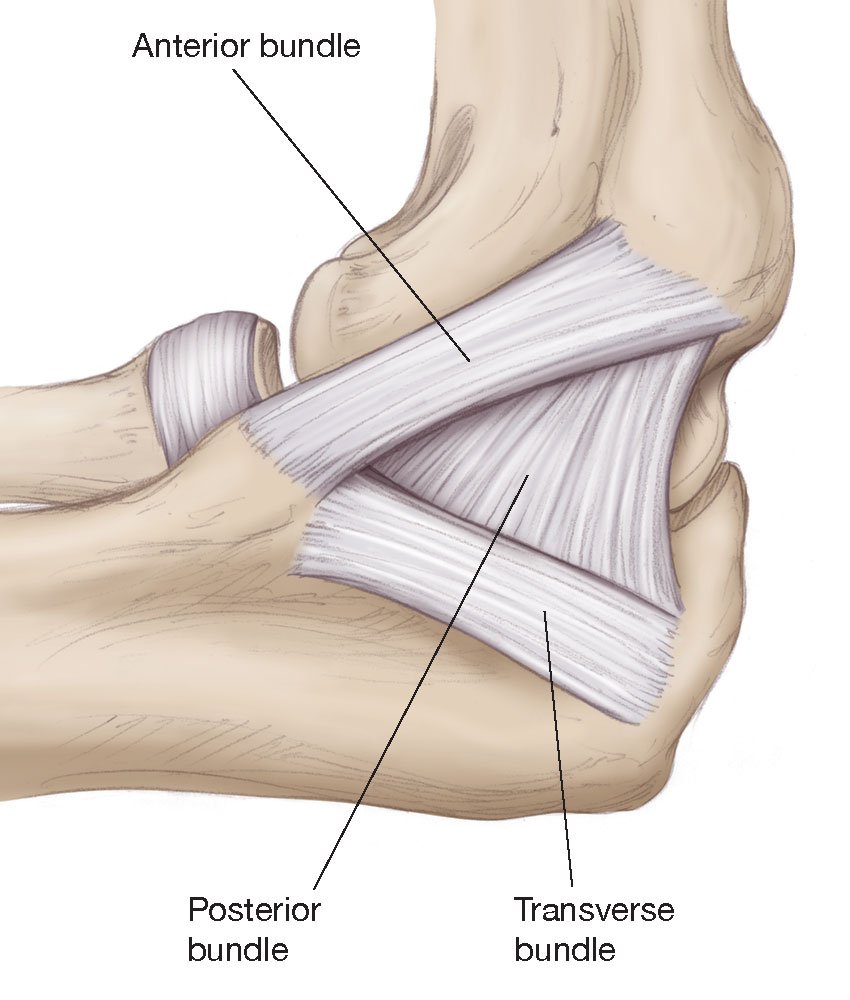

The UCL is comprised of 3 bundles: the anterior, posterior, and transverse bundles. The anterior bundle is the most important of the bundles, and it is the one that is typically injured and reconstructed in “Tommy John” surgery.

In the intact state, the UCL can withstand approximately 32 Newton-metres (unit of measurement for torque generated). In throwing a fastball, however, pitchers tend to generate up to ~64 N-m of torque across their elbow. By this biomechanical finding, one might suspect that a pitcher should tear their UCL anytime they attempt to throw a pitch. This, however, sheds light on the importance of the other dynamic stabilizers of the elbow during the throwing motion. The key dynamic stabilizer in this regard is the flexor-pronator mass (FPM)- a group of muscles and tendons which attach to the humerus bone on the medial aspect of the elbow and provide additional support to the ligament during throwing.

The flexor-pronator mass is a group of muscles and tendons that attach along the medial aspect of the elbow and are important secondary stabilizers of the elbow during overhead activities. They lie just superficial (above) to the UCL and support it.

Despite the supportive role of the flexor-pronator mass (FPM) in elbow stability, repeated forceful throwing (or compressive loading in a gymnast who is tumbling) can nonetheless lead to various injuries in the elbow. The most obvious, of course, is a tear of the UCL. A tear of the UCL can occur along a spectrum of severity- ranging from partial tears that may be amenable to non-surgical interventions to full-thickness tears that require repair or reconstruction of the ligament with a tendon graft (see further ‘Treatment’ details below).

(Left) Graphical representation of tear of the UCL. (Right) Coronal MRI sequences showing various injury patterns to the UCL including a distal tear where the ligament attaches to the ulna (A), mid-substance degeneration (B), and a proximal tear where the ligament originates from the humerus (C).

Aside from UCL tears, athletes who routinely subject the medial elbow to repeated stresses can also experience strains of the flexor-pronator mass. Since the FPM is constantly working to provide additional stability to the elbow during throwing, it can become overworked and sustain tiny micro-tears in the actual muscles and/or tendons. This is often a condition that can be managed non-surgically with adequate rest and an appropriate physical therapy program emphasizing re-strengthening of the full kinetic chain (force generators throughout the core, legs, and trunk and eventually working up towards the shoulder and elbow). Through a similar mechanism to FPM strains, young overhead athletes with open growth plates can experience an injury to the medial growth plate where the tendons of the FPM attach to the humerus bone. This is known as medial epicondyle apophysitis or “Little Leaguer Elbow”, and it is an injury/inflammation where the tendons attach to the bone although inflammation in the actual growth plate also tends to be present. Similar to FPM strains, Little Leaguer Elbow often resolves with a period of rest from throwing and an appropriate physical therapy program. Last, pitchers who have been throwing at a high level for many years can experience pain in their elbow from a condition known as valgus extension overload (VEO). This is a result of mild, early degeneration of the articular cartilage in the elbow from the repeated shear stress that occurs in the joint from long-term pitching. Though often painful, it can typically be treated with non-surgical interventions such as rest and occasionally with an injection in the elbow. If these measures do not allow a pitcher to continue throwing, a minor procedure to look inside the elbow with a small camera (elbow arthroscopy) and remove any impinging bone spurs may be appropriate and beneficial.

Symptoms of an Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tear

Ulnar collateral ligament injuries can occur acutely (sudden, immediate injury) during throwing (or, perhaps, tumbling in a gymnast). These injuries are notable for pain along the medial (inner) aspect of the elbow that is worsened by repeated attempts of activity. Additionally, athletes often feel or hear a “pop” in their elbow which is due to the sudden tear to the ligament. Occasionally, a minimal amount of swelling can be noted as well. Since the ulnar nerve lies very close to the UCL, it may become irritated from the surrounding inflammation and patients can experience a sensation of numbness or tingling along the inner aspect of their forearm and/or ring and pinky fingers.

Injuries to the UCL in throwers, however, actually tend to occur in a chronic (longstanding overuse) nature. Athletes may experience dull, achy pain along the inner aspect of their elbow after throwing a bullpen or several innings in a game. This pain typically occurs during the “late-cocking” phase of throwing as the arm is fully overhead and starting to accelerate to throw a ball. Pitchers also often notice slight drops in their fastball velocity or subtle loss of accuracy. They may never experience the classic “pop” from a ligament tear. This is because the ligament has been undergoing longstanding stretching and degeneration that makes it somewhat incompetent and non-functional in providing the necessary stability that pitching requires.

To diagnose a UCL injury, Dr. Koscso will perform a comprehensive medical history and physical examination. In particular, there are a few classic physical examination findings that are associated with UCL tears that will aid in diagnosis. Diagnostic imaging, including x-rays and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), may be requested to rule out any fractures or characterize the extent of the ligament injury, respectively.

(Left) The moving valgus stress test is a physical examination maneuver that assists in diagnosing UCL injury. (Right) Coronal MRI sequence showing a distal UCL injury (red arrow); note the healthy appearance of the proximal and midsubstance of the ligament (white arrow).

Non-Surgical Treatment

The option to pursue non-surgical treatment of UCL injuries is appropriate in select cases of partial-thickness tears in throwers or other overhead athletes, especially in younger patients with a shorter duration of symptoms. The exact location of the tear (proximal versus mid-substance or distal tears) also plays a role in the decision to pursue nonoperative interventions. As stated above, flexor-pronator mass strains as well as valgus extension overload are conditions that are typically treated through conservative measures.

Non-surgical treatment typically begins with pain-relieving measures such as icing the elbow and taking Tylenol/acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, etc. Rest from provocative activities (i.e. throwing) is appropriate often for a minimum of 6 weeks but can often be longer to allow the body to attempt to heal the injured UCL tissue. Initiating a sport-specific physical therapy program is crucial to optimize full-body biomechanics and posterior chain (core, legs, trunk) strength and stability, as often subtle weaknesses in these muscles lead to increased loads on the elbow during throwing and other overhead activities. Only once the athlete’s full body strength has been optimized through an appropriate physical therapy program should they begin an interval throwing program or other sport-specific graduated return to play protocol.

The question regarding injection options for partial-thickness UCL injuries often arises. While the role for an injection of platelet-rich plasma has shown some benefit in select orthopaedic studies related to UCL injuries, it can be thought of more as a potential augmentation to healing rather than an isolated treatment plan. It is still crucial than an athlete allows the adequate time-frame of rest as well as an appropriate physical therapy program to maximize full-body strength before returning to their sport.

Surgical Treatment

In athletes who have sustained full-thickness UCL tears or those who have persistent symptoms despite the above conservative measures for an appropriate time period, surgery is often the recommended treatment. If the decision to move forward with surgery is made by the patient/family with Dr. Koscso, there are a number of different treatment options listed below which may be performed in isolation or combination:

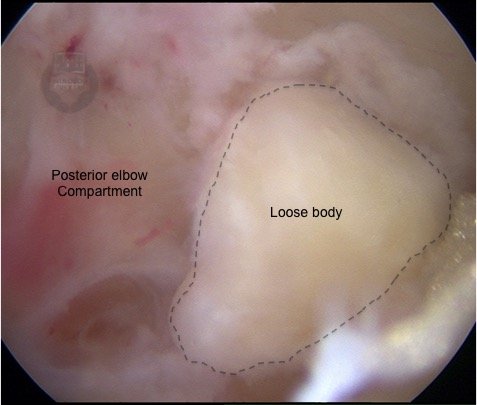

Elbow arthroscopy. In this minimally-invasive procedure, a camera (arthroscope) is inserted into the elbow joint to evaluate the articular cartilage for any secondary injuries related to UCL deficiency or chronic throwing. As stated above, older athletes often have mild, early cartilage degeneration in the back of their elbow related to the chronic shear stresses that occur in the joint as a result of years of throwing. This can be assessed with an arthroscopy procedure, and if any particular bone spurs are painful or limit the patient’s elbow motion, they can be removed. The second benefit to an elbow arthroscopy is that it allows for added confirmation of UCL deficiency as Dr. Koscso can stress the elbow while the camera is in the joint and confirm that the patient’s ligament is insufficient.

Elbow arthroscopy with the camera in the posterior compartment showing a large loose body (likely osteophyte or bone spur) which can be assessed and removed to improve elbow range of motion.

UCL repair. Some acute, full-thickness UCL tears may be amenable to repair of the injured ligament back to the portion of bone that it tore off from. This is accomplished with sutures placed through the injured ligament which are then reattached to the bone via specialized surgical anchors. This is an appropriate surgical option in younger patients with healthy ligament tissue. A surgical repair may be performed along with suture augmentation (see below) to reinforce the repair and minimize the chances of future re-injury. The benefit to repair, as opposed to ligament reconstruction with a tendon graft, is that it often allows for a quicker recovery and return to full sporting activity (approximately 6 months). The caveat to this repair option, however, is that the native ligament tissue must be of a healthy quality; unfortunately, as stated above, most lifelong throwers have chronic degenerative changes to their ligament which would preclude a repair procedure (in these instances, a ligament reconstruction is more appropriate). It is important to note that the decision to move forward with a repair (as opposed to a reconstruction) cannot be confirmed until the time of surgery when Dr. Koscso is directly assessing the quality of the ligament tissue.

UCL reconstruction. For full-thickness UCL tears or partial tears that have not responded adequately to non-surgical treatment, ligament reconstruction with a tendon graft is still considered the “gold standard” operative treatment. In this procedure, a tendon graft from elsewhere in the patient’s own body (often from the forearm or the knee) is used to recreate the native UCL. Bone tunnels are made in the ulna and humerus bones, and the tendon is passed through these tunnels and secured with sutures and/or specialized screws.

This procedure was first described by Dr. Frank Jobe in 1986 and nicknamed “Tommy John Surgery” after the first pitcher who underwent the operation and returned to pitching in Major League Baseball. Since its initial description, the technique of the surgery has evolved a great deal, and there are currently several specific techniques used related to bone tunnel configuration, graft choice, and whether or not to transpose (move) the ulnar nerve away from its normal location. While many of these technique modifications may play minimal to no role in overall prognosis and return to sport potential, Dr. Koscso performs the technique that has been shown in repeated orthopaedic studies to have the highest return to sport rates with the lowest complication profile and is the most-frequently used technique among MLB team physicians who treat UCL injuries (Watson, AJSM 2014; Erickson, Arthroscopy 2016; Clain, AJSM 2018; Griffith, AJSM 2019; Looney, AJSM 2021).

Graphic depiction of UCL reconstruction via a docking technique. In this technique, connecting bone tunnels are made in the ulna. A humeral socket tunnel is then made with small connecting Y-shaped tunnels. The tendon graft is passed through the ulnar tunnels and then “docked” into the humeral socket and secured.

Suture augmentation of UCL repair/reconstruction. As stated in our description of UCL reconstruction above, the surgical techniques related to the operation have evolved since Dr. Jobe’s initial article in 1986. One recent development in surgical technique is that of suture augmentation- adding a high-strength, collagen-coated suture tape to the repair construct to serve as an additional “check rein” or “safety belt” for the healing tissue. This technique has been shown in both biomechanical and clinical studies to provide added strength to the repair construct as well as allow for a quicker rehabilitation and return to sport (average 6.7 months) when used in appropriate tears in patients with healthy ligament tissue (Dugas, AJSM 2015; Dugas, AJSM 2019). More recently, the concept of adding suture augmentation to the tendon graft during a reconstruction procedure has also been proposed and shows promising data in early biomechanical studies in terms of increased strength of the reconstruction construct. Although long-term clinical data is currently lacking, it is an exciting topic for consideration as it relates to UCL reconstruction.

Graphic depiction of UCL repair with suture augmentation. In this procedure, a high-strength collagen-coated suture tape is added to the repaired ligament with the intention of increasing the strength of the repair construct and minimizing the chances of future re-injury.

Post-Operative Recovery

For a comprehensive reading of the expected post-operative recovery, including restrictions, physical therapy progressions, and return to sport guidelines after UCL repair/reconstruction surgery, please see our corresponding protocols on our physical therapy protocols page.

About the Author

Dr. Jonathan Koscso is an orthopedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist at Kennedy-White Orthopaedic Center in Sarasota, FL. Dr. Koscso treats a vast spectrum of sports conditions, including shoulder, elbow, knee, and ankle disorders. Dr. Koscso was educated at the University of South Florida and the USF Morsani College of Medicine, followed by orthopedic surgery residency at Washington University in St. Louis/Barnes-Jewish Hospital and sports medicine & shoulder surgery fellowship at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City, the consistent #1 orthopaedic hospital as ranked by U.S. News & World Report. He has been a team physician for the New York Mets, Iona College Athletics, and NYC’s PSAL.

Disclaimer: All materials presented on this website are the opinions of Dr. Jonathan Koscso and any guest writers, and should not be construed as medical advice. Each patient’s specific condition is different, and a comprehensive medical assessment requires a full medical history, physical exam, and review of diagnostic imaging. If you would like to seek the opinion of Dr. Jonathan Koscso for your specific case, we recommend contacting our office to make an appointment.